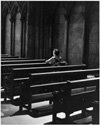

I hope everyone will sit down in a quiet spot, close their eyes, and listen as Psalm 51 is sung in my favorite setting, Allegri's Miserere.

Create in Me a Clean Heart, O God

To the choirmaster. A Psalm of David, when Nathan the prophet went to him, after he had gone in to Bathsheba.

51 Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your steadfast love;

according to your abundant mercy

blot out my transgressions.

2 Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity,

and cleanse me from my sin!

3 For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is ever before me.

4 Against you, you only, have I sinned

and done what is evil in your sight,

so that you may be justified in your words

and blameless in your judgment.

5 Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity,

and in sin did my mother conceive me.

6 Behold, you delight in truth in the inward being,

and you teach me wisdom in the secret heart.

7 Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean;

wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

8 Let me hear joy and gladness;

let the bones that you have broken rejoice.

9 Hide your face from my sins,

and blot out all my iniquities.

10 Create in me a clean heart, O God,

and renew a right spirit within me.

11 Cast me not away from your presence,

and take not your Holy Spirit from me.

12 Restore to me the joy of your salvation,

and uphold me with a willing spirit.

13 Then I will teach transgressors your ways,

and sinners will return to you.

14 Deliver me from bloodguiltiness, O God,

O God of my salvation,

and my tongue will sing aloud of your righteousness.

15 O Lord, open my lips,

and my mouth will declare your praise.

16 For you will not delight in sacrifice, or I would give it;

you will not be pleased with a burnt offering.

17 The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.

18 Do good to Zion in your good pleasure;

build up the walls of Jerusalem;

19 then will you delight in right sacrifices,

in burnt offerings and whole burnt offerings;

then bulls will be offered on your altar.

The following history is from Classical.net and provides a most excellent background on the history of the music,

Allegri's masterpiece was written sometime before 1638 for the annual celebration of the matins during Holy Week (the Easter celebration). Twice during that week, on Wednesday and Friday, the service would start at 3AM when 27 candles were extinguished one at a time until but one remained burning. According to reports, the pope would participate in these services. Allegri composed his setting of the Miserere for the very end of the first lesson of these Tenebrae services. At the final candle, the pope would kneel before the altar and pray while the Miserere was sung, culminating the service.

The idea of using a solemn setting of the "Miserere mei Deus" psalm likely started during the reign of Pope Leo X (1513-1521). Contemporaneous accounts relate the use of the Miserere in this way in the year 1514. The earliest surviving setting is dated 1518 and was composed by Costanzo Festa (c. 1490- 1545). Festa's Miserere was sung in the "falsobordone" style, which is an ancient and rather simple means of harmonizing on traditional Gregorian chant. His setting consisted of nine vocal parts split into two choirs, the first a five-part and the second a four-part, each alternating with the traditional Gregorian plainsong melodies, and then coming back together again for the last verse. Festa's setting was the first of twelve such settings collected in a two-volume manuscript preserved in the Pontifical Chapel archives. Ten more contributors, including Guerrero and Palestrina, are represented in these volumes before the final manuscript of Allegri's celebrated work, following exactly the same ensemble layout as Festa's original work and is likewise in the falsobordone style, closes the collection of twelve.

It was not long before Allegri's Miserere was the only such work sung at these services. With its soaring soprano parts (sung for centuries by castrati) and compelling melodic style, the work enjoyed almost immediate popularity. So impressed was some subsequent pope that the work thereafter was protected and a prohibition was placed on its use outside the Sistine Chapel at the appointed time. Chapel regulations forbid its transcription; indeed, the prohibition called for excommunication for anyone who sought to copy the work. In spite of this, by 1770 three copies were known to exist. One was owned by the King of Portugal; another was in the possession of the distinguished composer, pedagogue, and theoretician Padre Giovanni Battista Martini (1706-1784); and a third was kept in the Imperial Library in Vienna.

It is here that the first tale contributes to the mystique that has come to surround this work. The copy in the Imperial Library was brought to Vienna by Emperor Leopold I (1640-1705), who, having heard of the piece from dignitaries visiting Rome, instructed his ambassador to the Vatican to ask the Pope for a copy of the work for performance in the royal chapel. The Pope eventually obliged, but when the work was performed in Vienna, it was so disappointing that the Emperor believed he had been deceived, and a lesser work sent to him instead. He complained to the Pope, who fired his Maestro di Cappella. The unfortunate man pleaded for a papal audience, explaining that the beauty of the work owed to the special performance technique used by the papal choir, which could not be set down on paper. The Pope, understand nothing of music, granted the man permission to go to Vienna and make his case, which he did successfully, and was rehired. In fact, it is this elaborate performance technique, including improvised counterpoint, first employed soon after the work was written, that has been approximated in a recent recording by A Sei Voci on Astree.

The next famous story concerning the Miserere involves the 12-year-old Mozart. On December 13, 1769, Leopold and Wolfgang left Salzburg and set out for a 15-month tour of Italy where, among other things, Leopold hoped that Wolfgang would have the chance to study with Padre Martini in Bologna, who had also taught Johann Christian Bach several years before. On their circuitous route to Bologna, they passed through Innsbruck, Verona, Milan, and arrived in Rome on April 11, 1770, just in time for Easter. As with any tourist, they visited St. Peter's to celebrate the Wednesday Tenebrae and to hear the famous Miserere sung at the Sistine Chapel. Upon arriving at their lodging that evening, Mozart sat down and wrote out from memory the entire piece. On Good Friday, he returned, with his manuscript rolled up in his hat, to hear the piece again and make a few minor corrections. Leopold told of Wolfgang's accomplishment in a letter to his wife dated April 14, 1770 (Rome):

"…You have often heard of the famous Miserere in Rome, which is so greatly prized that the performers are forbidden on pain of excommunication to take away a single part of it, copy it or to give it to anyone. But we have it already. Wolfgang has written it down and we would have sent it to Salzburg in this letter, if it were not necessary for us to be there to perform it. But the manner of performance contributes more to its effect than the composition itself. Moreover, as it is one of the secrets of Rome, we do not wish to let it fall into other hands…."

Wolfgang and his father then traveled on to Naples for a short stay, returning to Rome a few weeks later to attend a papal audience where Wolfgang was made a Knight of the Golden Spur. They left Rome a couple of weeks later to spend the rest of the summer in Bologna, where Wolfgang studied with Padre Martini.

The story does not end here, however. As the Mozarts were sightseeing and traveling back to Rome, the noted biographer and music historian, Dr. Charles Burney, set out from London on a tour of France and Italy to gather material for a book on the state of music in those countries. By August, he arrived in Bologna to meet with Padre Martini. There he also met Mozart. Though little is known about what transpired between Mozart and Burney at this meeting, some facts surrounding the incident lead to interesting conjecture. For one, Mozart's transcription of Allegri's Miserere, important in that it would presumably also reflect the improvised passages performed in 1770 and thus document the style of improvisation employed by the papal choir, has never been found. The second fact is that Burney, upon returning to England near the end of 1771, published an account of his tour as well as a collection of music for the celebration of Holy Week in the Sistine Chapel. This volume included music by Palestrina, Bai, and, for the first time, Allegri's famous Miserere. Subsequently, the Miserere was reprinted many times in England, Leipzig, Paris and Rome, effectively ending the pope's monopoly on the work.

It is not known where Burney obtained his copy of the Miserere. It has been suggested that Maestro di Cappella Santarelli at the Vatican gave him a copy, which he checked against Padre Martini's manuscript when he visited Bologna. This is certainly possible, as is the alternative that he simply obtained a copy from Martini. However, both explanations seem unlikely given the papal strictures placed on copying the manuscript. Is it possible that Burney took Mozart's transcription, perhaps compared it to Martini's copy, and then published a cleaned-up version, minus the improvisations, and destroyed Mozart's manuscript to protect him as Catholic subject of the Holy Roman Empire? We may never know the whole story.

No comments:

Post a Comment